Philip Orr details the significance of the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant and the Fermanagh link through the Trimble family.

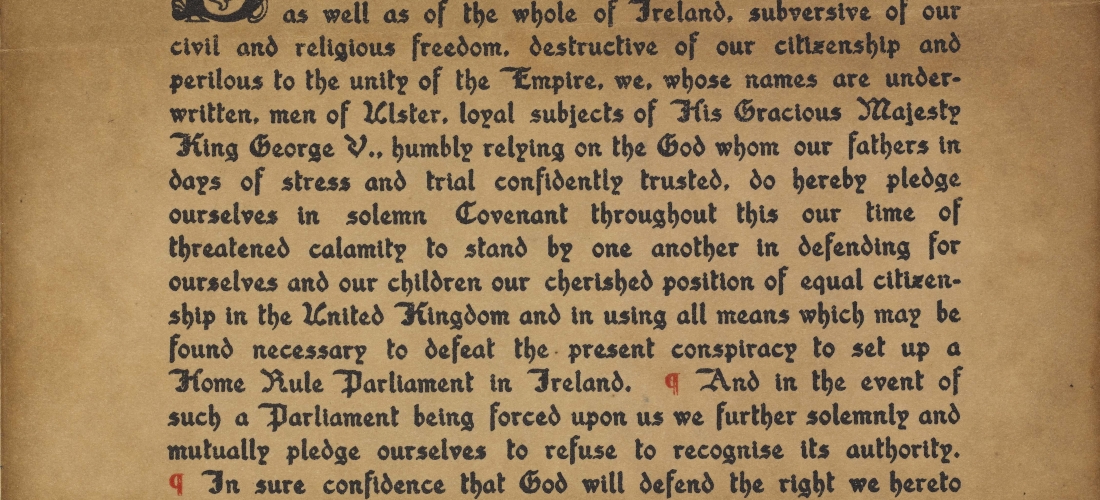

Souvenir copies of the Solemn League and Covenant were to be found in many Unionist homes throughout Fermanagh in the years after this famous political document had been signed. The Covenant was a pledge taken by the majority of Ulster’s Unionist population on 28th September 1912, promising resistance to the British government’s plans for a devolved government in Ireland, situated in Dublin. Unionists felt that Home Rule would harm their religious, economic and political well-being.

The signature on this copy belongs to William Egbert Trimble, who in 1912 was working as a young man in the family business, which consisted of the popular Enniskillen-based newspaper, The Impartial Reporter. Egbert’s father had been involved in political causes for a long time, including land reform. By 1912 he was an ardent Unionist member of the Urban Council and in the summer of that year he formed the Enniskillen Horse, which would style itself as the local ‘cavalry’ of the Ulster Volunteer Force, which was set up by the Ulster Unionist Council in the following year to resist Home Rule.

In 18th September 1912, a huge political rally was held in the town, addressed by the Unionist leader Sir Edward Carson. Then on 28th September, known to Unionists as Ulster Day, men and women throughout the county put their name to the Covenant at a variety of venues. As the Unionist cause was almost entirely supported by Protestants, church halls and Orange Halls were often the venues. In Enniskillen the main location for signing the document was the Town Hall. Throughout the day, the list of signatures steadily lengthened. Women had their own pledge known as The Declaration, which expressed similar sentiments. During Ulster Day, church services were also held, to seek divine aid in the struggle to defeat Home Rule, as expressed in the deeply religious text of the Covenant itself.

The document was regarded with a mixture of bemusement and dislike by the Nationalist majority in the county. They saw no reason for Protestants to fear devolution and looked forward to the arrival of an Irish parliament as the fulfilment of a long-held aspiration. They were troubled by the Covenant’s vow to use ‘all means which may be found necessary’ to achieve its objectives.

By the summer of 1914 the Ulster Volunteer Force had been matched by an Irish Volunteer militia dedicated to the implementation of Home Rule. When the First World War broke out in August, Fermanagh, like much of Ulster, was on the brink of civil war.